Lipoid Pneumonia:

Clinical:

Lipoid

pneumonia can be either exogenoous or

endogenous [4].

Exogenous lipoid pneumonia is caused by chronic aspiration or

inhalation of

mineral (paraffin, kerosene, or petroleum jelly), vegetable, or animal

oils

present in food, or oil based medications (such as nose drops). Once in

the

alveolar space, the oily substances are emulsified by lung lipase,

resulting in

a foreign body reaction. Predisposing conditions include neuromuscular

disorders

or structural abnormalities of the pharynx and/or esophagus that

predispose

them to aspiration [4]. Clinically patients with chronic lipoid

pneumonia are

frequently asymptomatic [4]. Symptomatic patients present with chronic

cough or

dyspnea, and less commonly fever, weight

loss, chest

pain, or hemoptysis [4]. Many patients are

elderly.

Lipoid pneumonia is a cause of chronic consolidation (other etiologies

to

consider for this finding include bronchoavleolar

cell carcinoma, tuberculous pneumonia, and

pseudolymphoma).

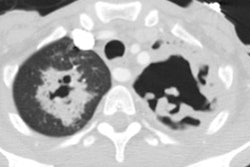

Acute exogenous lipoid pneumonia is uncommon and is typically caused by an episode of aspiration of a large quantity of a petroleum-based product [4]. It typically occurs in children (due to accidental poisoning), but can also occur in performers (fire-eaters) who use liquid hydrocarbons for flame blowing [4]. Patients present with cough, dyspnea, and low-grade fever [4].Radiographic opacities can be seen within 30 minutes of the episode of aspiration and will appear in most patients within 24 hours [4]. The opacities are typically ground glass or consolidative, bilateral, involve the middle or lower lobes, and are segmental or lobar in distribution [4]. Pneumatoceles can occur within 2-30 days and are more common in patients who have aspirated a large amount of mineral oils or petroleum-based products (such as can occur with fire-breathers) [4]. CT can reveal fat attenuation (-30 HU) in the areas of consolidation, but the associated inflammation often causes the fat to be less conspicuous [4]. The opacities resolve over 2 weeks to 8 months- resolution is generally complete, but mild scarring can occur [4].

Endogenous lipoid pneumonia results from lipid accumulation within intraalveolar macrophages in the setting of bronchial obstruction- "cholesterol pneumonia" [4]. It can also be seen in chronic pulmonary infection, pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis [5], or fat storage diseases [4]. Despite the presence of lipid, the consolidation does not appear of low attenuation on CT [4].

X-ray:

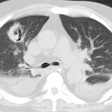

Radiographically, exogenous lipoid pneumonia is characterized by the

presence of lower lobe or right middle lobe [3] consolidations, mixed

alveolar

and interstitial opacities, and ill-defined or irregular mass-like

opacities

(due to chronic inflammation and fibrosis) [4]. On CT- the

consolidation can have fat

attenuation values (typically -30 to -80) and this will aid in

differentiation from other mass lesions. A "crazy-paving" pattern in

which well defined areas of ground-glass attenuation are superimposed

upon septal thickening has also been

described [3] (Ddx for this appearance

includes: Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis

and bronchoalveolar

cell carcinoma).

In

JRA, lipoid pneumonia shows multiple pulmonary nodules, mainly in a centrilobular distribution- which likely

represent

intra-alveolar and interstitial cholesterol granulomas

resulting from macrophage activation [5].

REFERENCES:

(1) AJR 1998; Franquet

T, et al.

The crazy-paving pattern in exogenous lipoid pneumonia: CT-pathologic

correlation.

170: 315-317

(2) Radiographics 2002; Gimenez A, et al. Unusual primary lung tumors: a radiologic-pathologic overview. 22: 601-619

(3) AJR 2008; Kim M, et al. MDCT evaluation of foreign bodies and liquid aspiration pneumonia in adults. 190: 907-915

(4) AJR 2010; Betancourt SL, et al. Lipoid pneumonia: spectrum of clinical and radiologic manifestations. 194: 103-109

(5) Radiographics 2011; Garcia-Pena P,

et al.

Thoracic findings of systemic diseases at high-resolution CT in

children. 31:

465-482

(6) AJR 2013; Nemec SF, et al. Lower lobe-predominant diseases of the lung. 200: 712-728