Pneumocystis jiroveci:

View cases of PCP pneumonia

Clinical:

Pneumocystis has been reclassified as a fungal infection [10] (although other authors refer to P. carinii as an unclassified organism having features of both protozoa and fungi [7]).

Patients with pneumocystis jiroveci (pneumocystis carinii or PCP) pneumonia typically present with the rapid onset of a non-productive cough and dyspnea/shortness of breath; although the infection can also be indolent. PCP infection develops in immunocompromised hosts- HIV, organ transplant recipients, patients with lymphoproliferative disorders, and patients on high dose corticosteroids [10]. In non-HIV patients that develop PCP infection, nearly 90% received corticosteroid therapy in the month preceding their pneumonia (steroids produce a decrease in CD4 cells in both the lungs and peripheral blood) [6]. The infection occurs most commonly toward the end of the patients steroid taper [10].

In HIV: PCP is the most common opportunistic pulmonary infection found in HIV patients in the United States [3], and is the initial manifestation of HIV in 40-60% of cases. About one quarter of these initial episodes prove fatal. PCP infection in HIV patients is unusual if the CD4 count is greater than 200 cells/uL. Typically patients have CD4 counts below 200, and PCP is even more common in patients with CD4 counts below 100 cells/uL [4]. An elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase level is very sensitive for PCP, but is non-specific as it may be elevated from a number of other processes as well [4]. Treatment for pulmonary infection is trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim or TMP-SMZ) or pentamidine. Prophylaxis with TMP-SMZ is performed to decrease the risk of developing PCP infection in AIDS patients [4]. Dapsone is a reasonable alternative prophylactic agent for patients with adverse reactions to TMP-SMZ. Aerosolized pentamidine prophylaxis is associated with a higher failure rate and offers no protection against toxoplasmosis infection [3].

In organ transplant: PCP most commonly occurs in the 4th-6th month following transplant and the mortality can be as high as 47% [10].

X-ray:

CXR: The CXR is normal in at least 10%, and possibly up to 40% of cases [11]. Classically, PCP causes bilateral hazy perihilar fine interstitial infiltrates which rapidly progress to diffuse air space consolidation over 3 to 5 days, but findings can vary from a patchy reticulogranular pattern to a bilateral perihilar alveolar process mimicking pulmonary edema. Upper lobe involvement is seen more commonly now and is associated with aerosolized pentamidine prophylaxis (extrathoracic disease is also more common in these patients as the agent suppresses pulmonary infection). Upper lobe predominance may also occur in patients not receiving prophylaxis [8]. Infection may progress to diffuse consolidation, developing a ground glass appearance. Thin-walled cysts can be seen in up to 10% of cases on radiographs, but are more commonly observed with CT [4]. Pleural effusions (2% of cases) and adenopathy are exceedingly rare. In fact, the presence of a pleural effusion should suggest another diagnosis.

Unusual presentations are increasing in frequency (between 5-10% of cases) due to effective prophylaxis and treatment [4]. Atypical manifestations include lobar consolidation with air bronchograms, a focal dense infiltrate, a miliary pattern, and a focal nodule/nodules which may have central low density or, very rarely, cavitation [4]. Nodules and masses are usually encountered relatively early in HIV infection, when patients are still capable of mounting a granulomatous response [8]. Parenchymal nodules in an HIV patient are still more commonly associated with other infectious (mycobacterial/fungal) or neoplastic etiologies [8]. Calcified granulomata due to PCP can occur in as a result of a chronic granulomatous response from the host [4].

A subset of patients will present with chronic PCP. These patients will have a prolonged clinical course with stable symptoms over a period of months to years. Affected patients deomstrate a chronic fibrosing response to the organism that is characterized pathologically by the presence of extensive interstitial fibrosis [9]. The primary radiologic features of chronic PCP are thickened septal lines, reticular opacities, traction bronchiectasis, and honeycombing. Cystic lesions may accompany these findings [9].

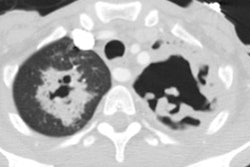

Computed tomography: HRCT is more sensitive than plain film for detecting the presence of pulmonary disease in HIV patients, and the negative predictive value of a normal CT is also extremely high (93%). On HRCT the most characteristic and common finding (up to 92% of cases) is the presence of areas of ground-glass attenuation which is typically most pronounced in the perihilar regions. A mosaic pattern of attenuation is very typical and interlobular reticulation within the areas of ground-glass can be seen- reflecting interstitial and interlobular septal infiltration by mononuclear cells and edema [4]. Interlobular reticulation is often the predominant finding during the sub-acute phase of the illness- reflecting clearing of the alveolitis with prominant septal lymphatics. Bilateral or unilateral parenchymal consolidations are a less common finding. The presence of thin (1-2mm) walled cystic spaces superimposed on the areas of ground glass attenuation are a common finding. The cysts are usually multiple and bilateral, have a random distribution, and show various degrees of wall thickness and different shapes [8]. The etiology of these cystic changes is not presently defined, but they are most likely small pneumatoceles. The incidence of cysts has been reported in between 10 to 40% of infected patients. Cystic spaces may resolve with successful therapy, but many cysts will persist. As some cysts resolve, they may remain as focal areas of parenchymal scarring which can mimic a focal mass lesion. Patients with PCP associated with cystic changes are at an increased risk for spontaneous pneumothorax secondary to cyst rupture (about one third of patients with cysts develop pneumothorax [5,8]). Patients with PCP who develop a pneumothorax have a significantly increased mortality rate compared to other patients with PCP pneumonia [8]. PCP related pneumothoraces are also often refractory to conventional chest tube treatment [8]. Persistent air leaks may require pleurodesis or chest tube drainage [8]. Mildly enlarged lymph nodes can be found at CT in about 18% of cases [8]. The presence of punctate calcifications within enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes is characteristic of disseminated PCP.

Scintigraphy: Gallium 67 scanning has also been used in the evaluation of patients with suspected PCP. Unfortunately, because of the cost of the exam, it's lack of specificity, and the delay (up to 48 hours) in scan interpretation, it is of limited usefulness [4]. The sensitivity of Gallium scanning for the evaluation of PCP in HIV patients has been reported to be as high as 90-95%. In PCP, there is generally diffuse increased pulmonary activity which is disproportionate to the clinical and radiographic findings. Unfortunately diffuse pulmonary Gallium accumulation can be seen in many other conditions which may affect HIV patients (CMV, MAI, M. tuberculosis, bacterial pneumonia, lymphoma, and cryptococcal infections) and the finding is non-specific (50-75%). Focal or patchy accumulation of the tracer can be seen in patients with PCP, particularly those who have been partially treated, but this pattern may also be seen in patients with superimposed bacterial infection. The specificity of the exam can be increased if one considers the intensity and distribution of the Gallium accumulation: Diffuse heterogeneous pulmonary activity which is more intense than the liver has a specificity for PCP between 95 and 100%. Diffuse homogeneous activity which is more intense than the liver has a slightly lower specificity for PCP of between 85 and 90%. Nodal activity suggests MAI, or TB infection. In patients who respond to treatment, pulmonary uptake of Gallium has been observed to return to normal.

Due to the presence of concurrent liver disease in these patients, determination of lung uptake relative to the liver may result in false-negative interpretations. A grading scheme of pulmonary uptake relative to the sternum should be more consistent.

- Grade 0: Normal

- Grade 1: Equivocal (Findings are probably not significant)

- Grade 2: Increased activity less intense than the sternum

- Grade 3: Increased and equal to the sternum

- Grade 4: Activity greater than the sternum

PCP is generally associated with at least grade 2 activity, and grade 3 and 4 are typically associated with significant disease.

Pulmonary capillary permeability using Tc-DTPA aerosol has also been evaluated as a means for diagnosing PCP infection. Increased permeability in patients with PCP results in a more rapid clearance of tracer from the lungs.

REFERENCES:

(1) Radiol Clin North Am 1994; Primack SL, Muller NL. High-resolution computed tomography in acute diffuse lung disease in the immunecompromised patient. 32(4): 731-744 (p.732)

(3) Curr Opin Pulm Med 1997; 3: 151-158

(4) Radiol Clin North Am 1997; McGuinness G. Changing trends in the pulmonary manifestations of AIDS. 35 (5): 1029-1082

(5) J Thorac Imaging 1998; Haramati LB, et al. Approach to the diagnosis of pulmonary disease in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. 13: 247-260

(6) J Thorac Imaging 1999; McGuinness G. Viral and pneumocystis infections of the lung in the immunocompromised host. 14: 25-36

(7) J Thorac Imaging 1999; Pennington DJ, et al. Pulmonary disease in the immunecompromised child. 14: 37-50

(8) AJR 1999; Boiselle PM, et al. The changing face of pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in AIDS patients. 172: 1301-1309

(9) Society of Thoracic Radiology Annual Meeting 2000 Course Syllabus; Boiselle PM. The changing face of PCP in AIDS patients. 111-114

(10) AJR 2005; Miller WT, Shah RM. Isolated diffuse ground-glass

opacity in thoracic CT: causes and clinical presentations. 184: 613-622

(11) AJR 2012; Lichtenberger JP, et al. What a differetial a virus

makes: a practical approach to thoracic imaging findings in the context

of HIV infection- Part I, pulmonary findings. 198: 1295-1304